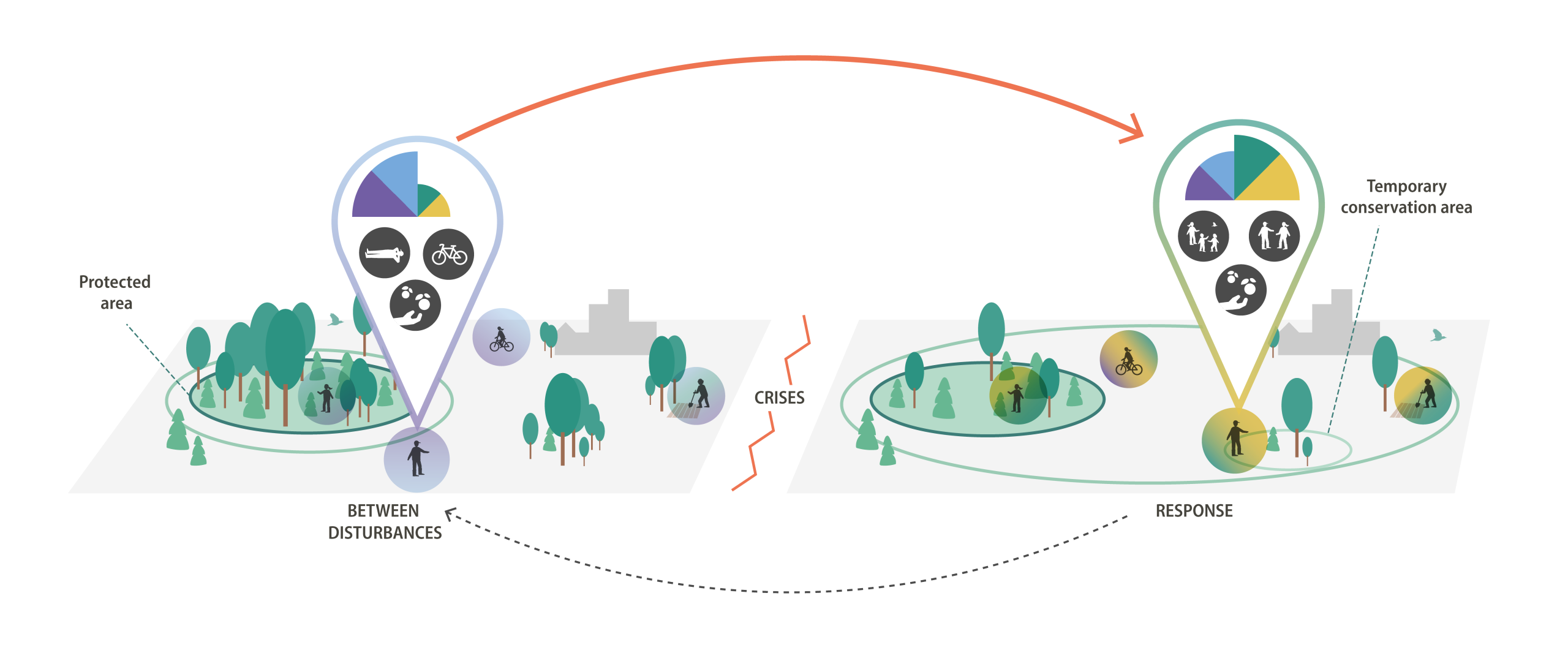

Figure on top: Crises and people–nature connections. Personal values (the pie tiles), needs (the color of the halo around the actors) and activities (the black and white symbols) in human–nature relationships are likely to be different during or just after and between crisis events. Crises change both the type of proconservation actions that are needed and where they are needed in larger, mixed protected, and nonprotected landscapes, as is indicated by the green ring outside the protected area, the functional conservation area. This has implications for how actors respond to the crisis and the role they may play in recovery and reorganization. The red and black arrows indicate the timeline of a disturbance cycle. (Graphic design: E. Wikander/Azote)

Our first big team paper is out!

Now you can read about the foundations of our project in the publication in BioScience on how we see that biodiversity conservation can be managed in more resilient ways: through considering and linking three types of connections —across land uses, between people and the landscapes they inhabit, and between sectors and governance levels. The conceptual figure sketches how activities and values that people hold in a landscape can guide recovery and restorative actions through crisis situations.

Connections play an important role in shaping landscape dynamics and in the ability of conservation practitioners to draw on resources outside their often limited mandates or authority. Focusing on disruptions, in this study, we discuss the current understanding of three interlinked aspects of conservation where active work with building and strengthening connections can help make recovery easier: landscape cohesion, societal appreciation and support for conservation, and the ability to rewire collaborations and bridge organizational and administrative boundaries. Specifically, we highlight how emerging insights on temporal shifts in connections, from spatial ecology to environmental psychology and crisis preparedness, inform and outline a research agenda for better situating conservation in complex landscapes undergoing frequent changes and disruptions.

We conclude with three key propositions for where further research and upgrades of conservation governance is needed:

- Guidance for when to invest in protected areas or to shift resources elsewhere.

- The evidence for the positive influence of a sustained, meaningful relation to nature for different conservation efforts (from protection to rehabilitation) is still tentative and in need of further research.

- Rapidly deployable and prenegotiated modes of governance—characterized by clear mandates, pooled resources, shorter decision chains, and intersectoral protocols—can offer critical capacity during disruptions and crises.

Full reference: